It used to be that, for Christmas, I’d do a production run of about a dozen of one thing or another. I’ve done toy blocks, cherry step ladders, loaded dice, folding side tables, bakers feet, bulletin boards, screw-top cans, garlic boxes, wavy bowls, … not to mention plenty of bad and worse syrup and jelly.

I haven’t done this for a few years, and I blame it on the usual suspects: I’m busy. It’s too much trouble. I don’t know how. There’s no time. I’m out of ideas. Bah humbug. How about: I’m out of excuses.

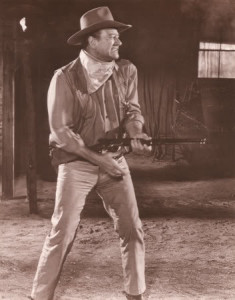

Remember grampa’s 3 rifles? There was the Big Gun I told you about, and a little one, too. And then there’s a Goldilocks gun that’s not too big and not too small.

It’s a Winchester model 1894, a .32 gauge lever-action firearm which, if you were surrounded by bad guys, you’d hold it at belt level and pump it between shots as fast as you can. Problem solved.

It fires a ‘special’ bullet. But a ’32-special’ is sort of like being ‘perfectly normal:’ Nothing special. It is actually different from regular .32 ammo, but the reason they called them ‘special’ seems to be mostly advertising: Gun people like their stuff ‘special’. Naturally, you can’t just walk into a store and buy these bullets (although they’ll special order them for you), so I bought a box online. Mail-order, no questions asked.

They are good looking units, too. They’re smaller than a lipstick, but the powder case is big enough to hold enough drugs or money for an emergency.

They are good looking units, too. They’re smaller than a lipstick, but the powder case is big enough to hold enough drugs or money for an emergency.

They’re perfect for silver bullets.

But how would I make one?

In college, there were gun nuts down the hall who used to reload their ammo in their dorm rooms. They’d replace the primers, weigh out the powder, and press the slug into the case with a reloading machine. Fifty or 100 bullets at a time. And nobody got hurt.

And over the years, Dad has shown me all kinds of cool stuff about lost wax casting.

So theoretically, I know how to do this.

Just to double-check, though, I got online and googled it, and it turned out that you need all kinds of supplies and equipment to make silver bullets. A furnace, a vacuum system, torches, crucibles, waxes, flux, silver, investment, clamps, vulcanizing rubber, presses, and safety equipment. It was early December, and I was thinking: ‘I gotta get this done by Christmas?’ Clearly, there’s no time for safety equipment.

Dad gave me a furnace several years ago, and it’s been sitting in the back of Chuck since we moved. It weighs a ton, but it still works.

And a few years ago, I turned a 3/4 hp vacuum pump into a dryer for my hearing aid. I keep it on my nightstand and run it every night. (just kidding)

Plus, I’ve got torches out the wazoo, so my checklist already starts out with “check check check,” and I’m off to a good start.

So I got online and wrote a check for $100 for a crucible, some wax and investment powder, and got to work.

The first task was to disassemble a bullet so I could take measurements. It took me 3 holding jigs before I got one apart, and I was thinking that if everything is going to be this difficult, then the schedule is looking mighty tight, indeed. Once I got it apart, I realized that – yikes! – this thing is full of gunpowder! I was doing this work at the same bench where I usually do my welding, so how do I dispose of it? In the end, I dumped it in the fire-pit out back, and I’m hoping that even after a winter’s worth of wetness, our first campfire of the Spring will have a little extra sparkle.

The first task was to disassemble a bullet so I could take measurements. It took me 3 holding jigs before I got one apart, and I was thinking that if everything is going to be this difficult, then the schedule is looking mighty tight, indeed. Once I got it apart, I realized that – yikes! – this thing is full of gunpowder! I was doing this work at the same bench where I usually do my welding, so how do I dispose of it? In the end, I dumped it in the fire-pit out back, and I’m hoping that even after a winter’s worth of wetness, our first campfire of the Spring will have a little extra sparkle.

Now if I had a silver bullet, I’d want to be able to take it apart, put stuff inside, and put it back together (with one hand behind my back). So I needed to find a way to hold the bullet in the casing, and a friction fit was probably not going to work. How about if I thread it into the case? Bad news: Goldilocks is some weird diameter that’s too big for 5/16″ or 8mm threads, but too small for 3/8″. And although I could thread the bullet on the lathe, I couldn’t turn the case. Too small and too thin.

What to do? The prospect of ‘gift cards for all’ focused my mind.

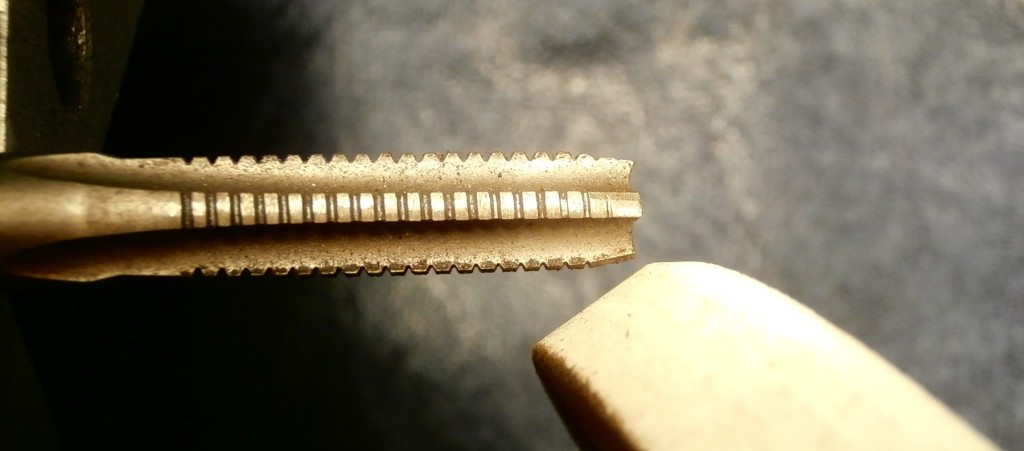

When I first started metalworking, I made myself the world’s clunkiest tool post grinder, but it vibrated something fierce on my old lathe, so I never really used it. It runs fine on my big lathe, though, so I decided to try grinding back a 3/8″ tap to a special flat-top profile that will mate with a bullet lightly scored by a 3/8″ die. I did the math, and I needed the flat bottom of the thread to be about 4 mils deep into the inside face of the casing, which is only 10 mils thick to begin with, and it ‘gives’ when you squeeze it. This was going to be hard.  It took me 2 tries to grind a tap to the right diameter, and then I had to grind back the clearance angles so it could cut cleanly.

It took me 2 tries to grind a tap to the right diameter, and then I had to grind back the clearance angles so it could cut cleanly.  It didn’t work.

It didn’t work.

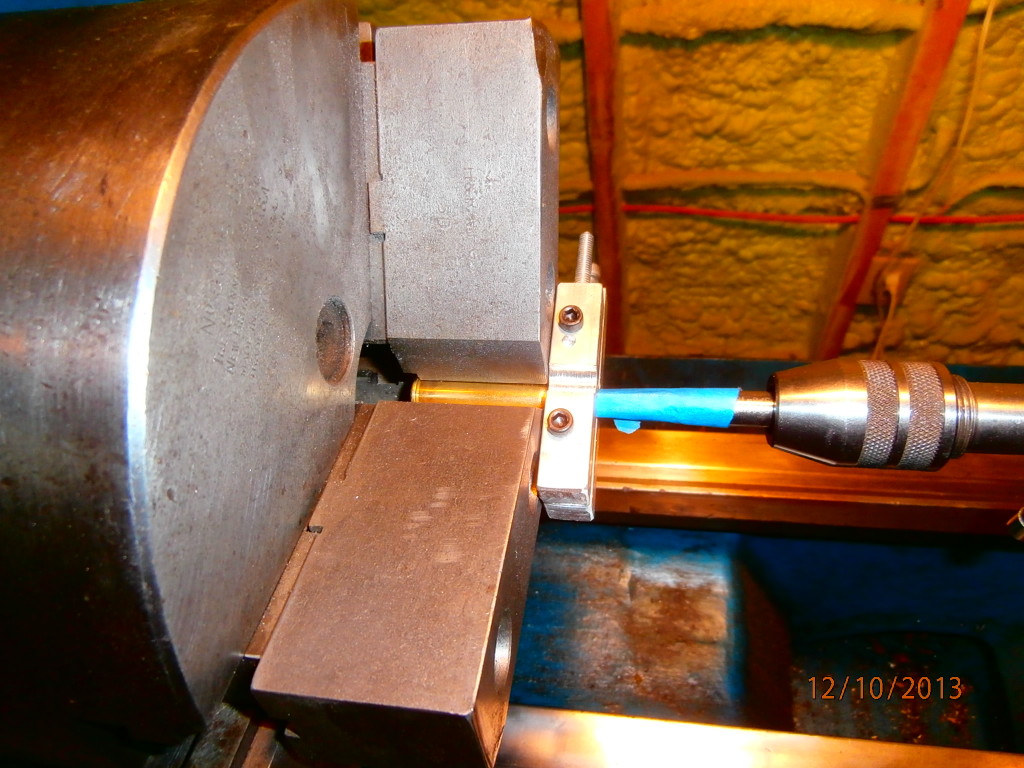

With such shallow threads, the tap didn’t have the ‘grab’ it needed to feed itself into the hole, and it cut more like a reamer than a tap. So I swapped my lathe around so my tailstock was in the middle and then I bumped my cross-feed table into it, driving it at 16tpi. The tailstock center drives the tap into the hole at just the right speed. It still didn’t work.

It still didn’t work.

The casing was too thin and flexible, and it just flexed out of the way instead of letting the tool cut it. So I made a collar and clamped it around the neck of the casing to keep it from bending.  And it came out perfect! Wow. Better than expected. Woohoo!

And it came out perfect! Wow. Better than expected. Woohoo!  So I banged out 11 more. Bam bam bam!

So I banged out 11 more. Bam bam bam!

OK, so I’m half done, and that only took me 2 days. What’s next?

Wax.

Wax.

I decided I don’t have time to mess with rubber molds, which means that for every bullet I want to cast, I need to make a single-use wax blank on the lathe. Because the bullets are threaded, the diameter has got to be pretty accurate. And because the mating thread is only 4 mils deep, it’s got to be rrreally accurate. But I wasn’t sure exactly what that number’s got to be, because … because there’s a measurement involved that I just can’t seem to pull off. Oh well. So I decided to shoot for .328, and then ran the wax a few turns into a 3/8″ die and got a decent fit.

I used a paint scraper to carve a freehand curve on each blank. Anyone got a problem with using a 3000# lathe to turn a 2 gram piece of wax?

I used a paint scraper to carve a freehand curve on each blank. Anyone got a problem with using a 3000# lathe to turn a 2 gram piece of wax?

I made 12 wax bullets and mentally patted myself on the back for making a spare, since I only had 11 threaded casings. So if anything goes wrong, I’m golden.

I mounted them, 4 at a time, on sprues so they could be cast. I used a couple of configurations that, it seemed to me, ought to work. And if anything goes wrong with the first casting, I’m golden, because I’ve got 2 more queued up.

I mounted them, 4 at a time, on sprues so they could be cast. I used a couple of configurations that, it seemed to me, ought to work. And if anything goes wrong with the first casting, I’m golden, because I’ve got 2 more queued up.

I gerry-rigged my hearing-aid dryer with a taller vacuum chamber so I could de-bubble the investment plaster. (I carefully cleaned the kitchen mixer so the holiday baking wouldn’t taste like gypsum.)

I gerry-rigged my hearing-aid dryer with a taller vacuum chamber so I could de-bubble the investment plaster. (I carefully cleaned the kitchen mixer so the holiday baking wouldn’t taste like gypsum.)

And I fired up the furnace directly under the exhaust inlet to the (unfinished) house air exchanger so the whole house wouldn’t stink and give away my secret project in the basement.

Well, I don’t know what went wrong, but the first cast did not work.

The directions say to heat to 300F for a couple hours.

The directions say to heat to 300F for a couple hours.

Then to 700 for an hour.

Then to 1350 for a couple hours.

Then to let it ‘soak’ for an hour.

And then to pour the cast.

And I had every intention of doing exactly that, but the furnace seemed kind of feeble, and it would only go so hot, and it wheezed to a halt at 850F after 6 hours. So, with little to lose, I decided to melt some silver and pour it.

The directions also say to use an oxyacetylene torch to melt your silver grains in a crucible and to make sure it’s not just melted, but good and hot when you pour it into the mold. And, again, I had every intention of doing exactly that, but the oxygen tank chose that exact moment to run out, and the torch started getting erratic. So, thinking on my feet, I panicked and poured the silver melt down the sprue hole.

The directions also say to use an oxyacetylene torch to melt your silver grains in a crucible and to make sure it’s not just melted, but good and hot when you pour it into the mold. And, again, I had every intention of doing exactly that, but the oxygen tank chose that exact moment to run out, and the torch started getting erratic. So, thinking on my feet, I panicked and poured the silver melt down the sprue hole.

Now think about this melted silver, being poured down a warm hole in the mold of my wax. Silver melts at 1800F and the mold is 1000° colder than that, so most of it solidifies on contact, and what little is left is supposed to flow thru a full half inch of 1/8″ dia sprue and then fill up an un-vented, gas-filled, bullet shaped chamber. And leave a shiny, smooth finish. Are you kidding me? My wax is all wrong. What was I thinking?

So far, that’s 2 forced errors and a stupid mistake, and I can live with that. But what rrrreally pisses me off is that I put all 3 of my wax-in-plaster flasks in the furnace on the trial run, and melted them all out, so now not only am I back down to zero wax bullets, I’m almost out of wax!

So far, that’s 2 forced errors and a stupid mistake, and I can live with that. But what rrrreally pisses me off is that I put all 3 of my wax-in-plaster flasks in the furnace on the trial run, and melted them all out, so now not only am I back down to zero wax bullets, I’m almost out of wax!

I’m not so golden after all.

When Dad learned to cast, he was mentored by Bob Winston. Bob said that when Dad first showed up with a failed casting and asked what he’d done wrong, the answer was ‘just about everything,’ and they became fast friends. So now I had my own casting disaster on my hands. I was stumped and dejected and didn’t know what I was doing wrong. I was thinking Christmas is going to be a bust this year, and I put out an SOS to Dad. And when he replied: “You have made every mistake possible,” I knew what he was really saying was that I’m a chip off the old block.

For all the time I’d spent googling how to do this, getting a little advice from Dad was like having my own personal Siri – minus the voice recognition. He told me exactly what to do:

– Run the furnace on 240V.

– Run the furnace on 240V.

– Use bigger sprues.

– Add vents.

– Fill from the bottom.

– Get it good and hot.

For once, I did exactly that, and I was ecstatically happy with this imperfect casting.

Actually, that one was supposed to have 3 bullets on it, but one of them fell off in the vacuum chamber because my joints were weak. So I practiced my wax welding and, from there on, every wax and every pour was better than the last one.

So I was over the hump and the hard part was done, but finishing the job didn’t go smoothly. The surface of the castings were way rougher than I’d expected, and they wobbled off-center because the threads were not perfectly axial. So what I’d hoped would be a job for steel wool quickly became another machining nightmare.

I learned, for example, that cast silver, in violation of the laws of physics, is both ductile and brittle at the same time.

And I learned that .32 special casings are not engineered for torque.

In the end, elbow grease and a mill bastard file were the best tools for the job, and I probably filed $20 worth of silver onto the floor before the bullets finally looked dangerous.

There are 2 ways to use a silver bullet:

For once-in-a-lifetime problems, fire the bullet. The primer (just so you know) is live and, if you hold it close and hit it just right, it will explode and, because the bullet is screwed in, the shrapnel will kill you.

Problem solved.

For run-of-the-mill problems, get comfortable, light a candle and settle back. Hold your silver bullet close to you and relax. Breathe deep, as though you’re curing a case of hiccups. And then follow the directions in the Christmas poem inside it.

And your problem will be solved.

This was a great project. In less than 3 weeks, I turned a crazy idea into a cool gift and just about every step of the way was a new problem to solve.

I made a baker’s dozen of them and gave 12 away.

Because if anyone needs a silver bullet, it’s me.

One Response to The Silver Bullet